Pastor Joe Britton

St. Michael’s Church

III Easter

“Were not our hearts burning within us while he was talking to us on the road …” (Luke 24)

Last week, we looked at the story of “doubting Thomas” through the lens of stress, and talked about how in these times we might better understand him as “stressed out Thomas.”

Today, I’d like to take a similar tack with the story of the Road to Emmaus, reading it as a story of feeling disoriented. Like the story of Thomas, it is a familiar Easter episode. Two disciples are walking on Easter afternoon along the road to Emmaus, a town just outside of Jerusalem, talking about all that has happened in the city – Jesus’ arrest, his trial, and of course his death. I imagine that their reasons for going are that they are trying to escape it all, leaving the chaos of the city for a greater calm in the country. But now new rumors are circulating that some women have been to the tomb and there had a vision that Jesus is alive. These disciples’ heads must be spinning: the text is pretty insistent that they are “talking and discussing,” trying to make sense of it all.

And then suddenly, Jesus himself catches up with them along the road, but in their disoriented frame of mind they don’t even recognize that it is him. They unburden themselves to this stranger about all that they have seen and heard. And then, starting at the beginning, Jesus tries to explain to them how all of the scriptures have been fulfilled in him. And yet – they still don’t realize that it is he who is with them.

You know the outcome already: only when the three of them stop at an inn for supper, and he breaks bread with them, do they suddenly realize who it is—but in that moment he vanishes from their sight, and they race back to Jerusalem to share the news of their encounter.

If Thomas could not believe because he was under such stress, it seems to me we might think that these two unnamed disciples could not recognize him, because they were feeling so disoriented. So much has happened that has turned their world inside out and upside down, that they just aren’t able to see or think very clearly.

That, too, is a feeling many of us share right now. We wake in the morning, not sure of what day of the week it is. We think we ought to get to work, but are not sure of what that looks like while we are confined at home, or with so much of society closed down. We listen to the news, and hear wildly conflicting reports of what is and isn’t a safe way forward. We long for companionship, but must remain distanced, for how long, we’re not sure. And our heads feel as if they are spinning.

Or, perhaps we are among those who continue to perform the essential tasks that keep the rest of us going. But there to, the sense of isolation from so much of the community, and the disruption of so much of life undermines our mental equilibrium.

So being in a similar state of mind, what happens to the two disciples is hardly surprising, Their encounter with Jesus is all part of their disorientation, until they experience something that is familiar and intimate: the breaking of bread. In that moment, their confused hearts and minds are given a new sense of bearing, and suddenly the meaning of all that has happened falls into place with complete clarity.

But what they discover, is more than the simple fact of Jesus having been with them: they discover that Jesus’ presence, paradoxically takes the form of absence. Recognizing him, they also lose sight of him, except that even then they continue to feel his presence in the space that is between them. So it isn’t an absence of emptiness, but an absence of filling, enveloping them with the sense of purpose through which they are again able to understand their own life.

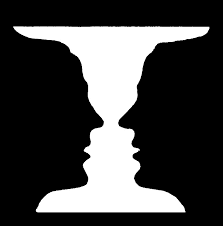

Jesus’ presence, you might say, is a bit like the empty space in one of those images of two faces looking at each other, which in silhouette form a cup [hold up the image]. The space would be nothing at all, without both faces framing it. But with them, it is a clear shape that holds the promise of something social and mutually binding between them.

We are accustomed to thinking of finding Jesus in the Other, and that is true enough. But the story of Emmaus also suggests that we find Jesus in the space between ourselves and the Other: a space which we both contribute to shaping and occupying. Without the presence of an Other (whether that is a spouse, or a child, or a parent, or a lover … or a stranger), it’s hard to know what the space is that we ourselves occupy, hard to know who we are.

In this time of being distanced from one another, we might think of the space that separates us not as a burden or pain to be born, but as a sacred space, a space which by honoring it, we together shape into a vessel of care, hope and solidarity. Perhaps the space we keep between us, is filled more than ever by Jesus himself.

Playing off of the image of the two faces that I showed you a moment ago, the poet Rowan Williams penned these lines in his poem, “Emmaus”:

Between us is filled up, the silence

is filled up, lines of our hands

and faces pushed into shape

by the solid stranger, and the static

breaks up our waves like dropped stones.

So it is necessary to carry him with us,

cupped between hands and profiles …

In short, our lives are given their orientation by one another – or rather, by the presence that is in the space that is between us, that mysterious presence that fills the gap, as present at this very moment as the air we breath—even now, when so much of life otherwise seems distant, shut off, and disorienting. Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed